In these troubled times… But aren’t all times a bit troubled? When I was in my 20s or 30s, I remember asking my mom, ‘When did life settle down – when did you get things figured out and on track?’ She had a good hearty laugh for my answer.

It was probably after that when I took my first trip in a new job, to Dar es Salaam in July-August 1998. Alert readers may know where this story is going. Yes, I was there, providing technical assistance in the USAID offices (actually, sending email home about my flight that evening) when suicide truck-bombers in Nairobi and Dar killed a lot of people. My colleague and I heard what sounded like an airplane breaking the sound barrier, and in an offhand way wondered aloud who would be doing that in Tanzanian airspace. A few minutes later we learned the error of our assumption.

The point for this note is that there was a LOT of chaos, and (even at the time) I found it fascinating how differently individuals reacted to the huge uncertainties we all instantly faced, and under which we had to make a great many decisions – wait, act, which action, what info to trust, how to reconcile conflicting stories, when to move, where. I particularly remember one fellow, being very loud and decisive, but wrong, in the first moments, but the rest of the day was a rolling sequence of fast, critical, potentially life-risking decisions made, large and small, every few minutes.

Character is revealed in these moments, but character is also built, or fails to build, through each person’s preparation and navigation of any crisis – the slow and boring ones as well as moments of high drama – and how we process the whole of the experience both during and after living through it.

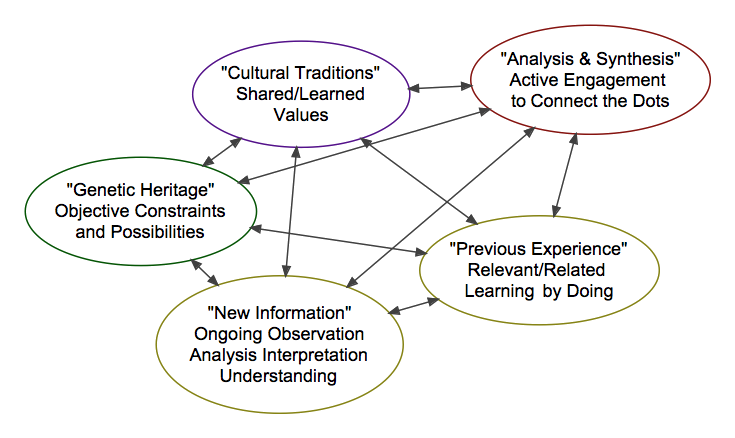

John Boyd created a sophisticated strategic learning system that is sometimes oversimplified to four steps – Observe, Orient, Decide, Act – abbreviated as OODA. As one way to approach decision-making under uncertainty, OODA explicitly integrates constructive ways to think about new information, especially when it is complex, partial, unclear and uncertain, multidimensional, possibly misleading, and, to the novice eye, entirely overwhelming. The context is the cockpit of a jet fighter – consider all of the instruments, all of the distractions, how fast you are going, 360° of space for enemy action. Now add an opponent, or several. How can you focus on noticing everything you need to analyze in order to understand what’s happening and thus what your possible/best options are and, finally, which one you should choose – and keep doing this in every instant as the battle unfolds?

This was a huge challenge, and narrowing the field of fighter jet pilots only to those with the natural ‘right stuff’ would be a very small pool. Boyd was a kind of natural genius, though, who realized there are many learnable, trainable, habitual pieces of such situations, and that most of us can get better at navigating them, and succeeding through them, with the right tools. More than insight, he worked his whole life to operationalize, mathematically model, and teach others the skills and tools. He is one of my heros.

I’m no Boyd, and hadn’t heard of him in August 1998, but in retrospect it’s obvious to me that my abilities and experiences prior to that episode had enormous impact on how the day and following days unfolded for me, the choices I made, and personal outcomes. Since stumbling across Boyd’s neat synthesis, I’ve been more conscious of building in new competencies and ever-strengthening a mindset for constructive action whether I’m in a hurricane, on the periphery of war zones, or dealing with normal life events such as difficult people, job loss, or death of a parent. It’s also a job tool for me (having worked in many peace-precarious situations [again, really, isn’t peace precarious everywhere?] around the world), and I think it should be more familiar to everyone, especially anyone working in the evaluation context. The ‘scientific’ approach deriving from a lab setting is fundamental and crucial for valid and reliable learning, but is ill-suited for real life ‘social’ experiments, policy interventions, program implementation, and results assessment. In the real political economy, intended improvements are still contested changes, and they roll out and are resisted in a context of strategic opposition, imperfect knowledge, and dynamic shifts over time. OODA is a toolkit that, with practice, builds capacity to narrow uncertainties and respond nimbly to new information toward more optimal outcomes.